A Brief History of the Flagg-Rochelle Public Library

The Flagg-Rochelle Public Library District was founded in 1892 and has been in the same location for more than 100 years.

Our Story

Humble Beginnings

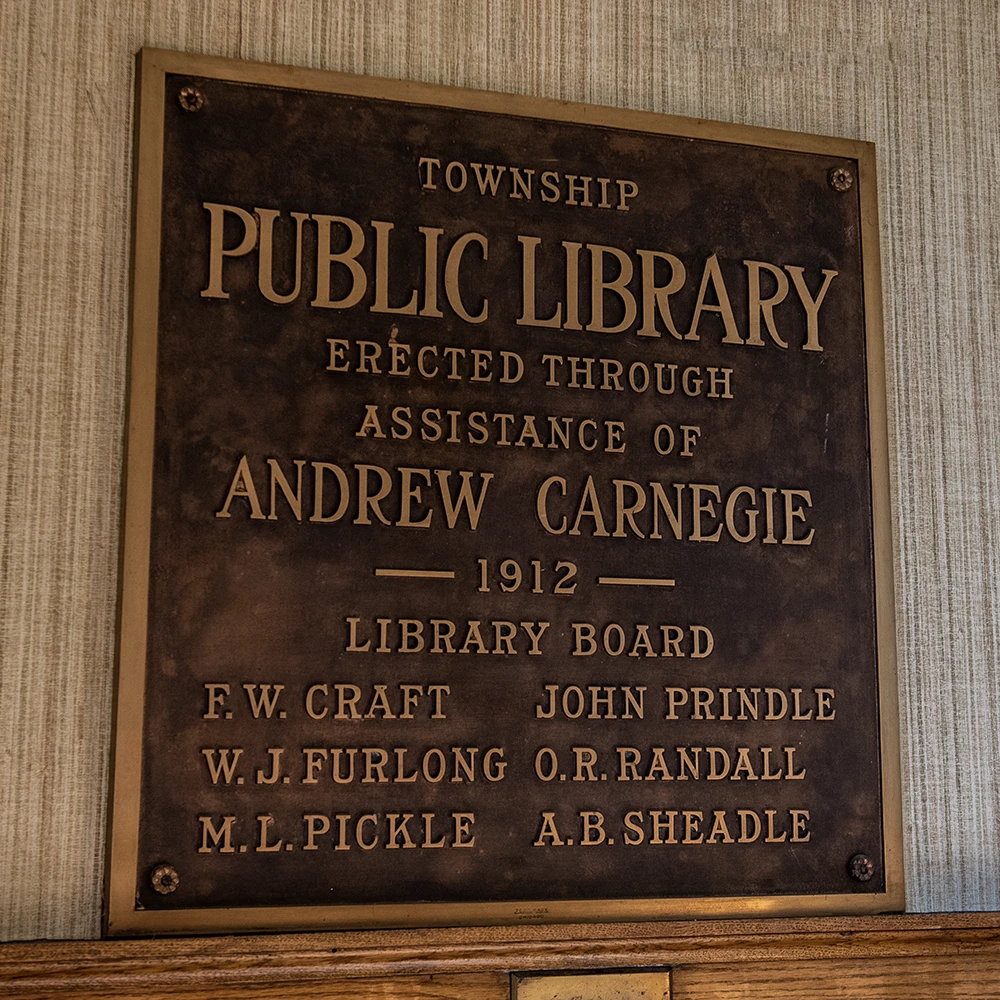

The Rochelle-Flagg Public Library was voted into existence in an April 1889 local election, and the library began operations in 1892 out of a single room in the Rochelle Town Hall, which is now the Flagg Township Museum. In 1912, after years of steady growth and community interest, the library board secured a $10,000 Carnegie Grant to help fund the construction of a standalone library to house the growing collection of volumes and resources.

Our Story

Humble Beginnings

The Rochelle-Flagg Public Library was voted into existence in an April 1889 local election, and the library began operations in 1892 out of a single room in the Rochelle Town Hall, which is now the Flagg Township Museum. In 1912, after years of steady growth and community interest, the library board secured a $10,000 Carnegie Grant to help fund the construction of a standalone library to house the growing collection of volumes and resources.

"A library outranks any other one thing a community can do to benefit its people. It is a never failing spring in the desert.”

— Andrew Carnegie

A Building for the Ages

In an effort to construct a building that would set itself apart from other libraries of the time, the library board hired the acclaimed architecture firm of Claude and Starck out of Madison, Wisconsin to design the structure. As a student of Frank Lloyd Wright and formerly of the famed Chicago architecture firm Adler and Sullivan — whose buildings include the Chicago Stock Exchange and Auditorium Theatre in downtown Chicago — Louis Claude designed the Flagg-Rochelle Library in the Prairie style that Wright pioneered.

A Building for the Ages

In an effort to construct a building that would set itself apart from other libraries of the time, the library board hired the acclaimed architecture firm of Claude and Starck out of Madison, Wisconsin to design the structure. As a student of Frank Lloyd Wright and formerly of the famed Chicago architecture firm Adler and Sullivan — whose buildings include the Chicago Stock Exchange and Auditorium Theatre in downtown Chicago — Louis Claude designed the Flagg-Rochelle Library in the Prairie style that Wright pioneered.

The single-story design includes a raised basement, and the main floor reading room is complete with a fireplace and built-in oak bookshelves. Decorative leaded glass windows form a continuous band around the reading room, and a meeting room, complete with a small stage, in the raised basement is accessible through its own entrance.

The exterior features a continuous limestone stringcourse around the building, along with distinctive cream-colored frieze panels and a bright orange tile roof.

At the time of its construction, the majesty of the building’s design was rivaled only by its aura of whimsy. Early photos of the library during the warmer months show a fish pond on the front lawn. When Betty Neal began working at the library in 1948, she found a hole in the floor of the library and a number of half-empty boxes of fish food. It was explained that the hole had been for a pipe for the indoor fish tank.. During the winter months, fish from the outdoor pond would be transferred to the indoor fish tank, and local residents would often bring their own fish to ‘winter’ at the library.

The single-story design includes a raised basement, and the main floor reading room is complete with a fireplace and built-in oak bookshelves. Decorative leaded glass windows form a continuous band around the reading room, and a meeting room, complete with a small stage, in the raised basement is accessible through its own entrance.

The exterior features a continuous limestone stringcourse around the building, along with distinctive cream-colored frieze panels and a bright orange tile roof.

At the time of its construction, the majesty of the building’s design was rivaled only by its aura of whimsy. Early photos of the library during the warmer months show a fish pond on the front lawn. When Betty Neal began working at the library in 1948, she found a hole in the floor of the library and a number of half-empty boxes of fish food. It was explained that the hole had been for a pipe for the indoor fish tank.. During the winter months, fish from the outdoor pond would be transferred to the indoor fish tank, and local residents would often bring their own fish to ‘winter’ at the library.

Designed in Frank Lloyd Wright’s revolutionary Prairie style, the library so closely resembles his work that it is often confused for a Wright design.

Growing Pains

Decades of continued growth and use saw the library’s collection balloon to more than 30,000 volumes; the original design allowed for about 16,000 volumes. By 1964, the children’s department had moved into the basement, and by the mid-1980’s it was clear the library had outgrown its original design and needed to expand.

To commemorate 100 years of service, the library completed a $1.8 million addition in 1989 that increased the square footage of the original building to more than 20,000. Designed by the Chicago architecture firm Frye Gillian Molinaro, the addition also included careful restoration work on several of the library’s original glass windows to help preserve the historical integrity of the space while also updating it for modern-day use.

The biggest highlight of the project was the addition of new frieze panels that were actually molded from original panels the library had loaned to the Detroit Lakes Public Library in Minnesota more than 100 years prior.

Growing Pains

Decades of continued growth and use saw the library’s collection balloon to more than 30,000 volumes; the original design allowed for about 16,000 volumes. By 1964, the children’s department had moved into the basement, and by the mid-1980’s it was clear the library had outgrown its original design and needed to expand.

To commemorate 100 years of service, the library completed a $1.8 million addition in 1989 that increased the square footage of the original building to more than 20,000. Designed by the Chicago architecture firm Frye Gillian Molinaro, the addition also included careful restoration work on several of the library’s original glass windows to help preserve the historical integrity of the space while also updating it for modern-day use.

The biggest highlight of the project was the addition of new frieze panels that were actually molded from original panels the library had loaned to the Detroit Lakes Public Library in Minnesota more than 100 years prior.

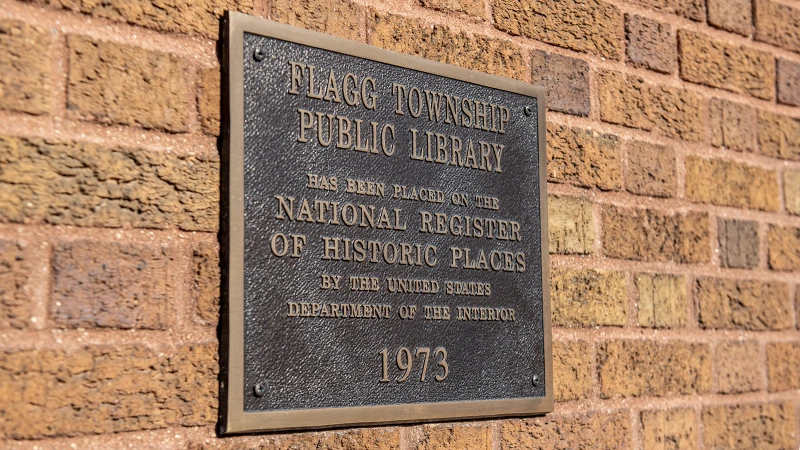

A National Landmark

The Flagg-Rochelle Public Library was added to the National Registry of Historic Places in 1973 in recognition of its historical and cultural significance. Today, the library serves more than 13,000 residents and an increasing number of non-residents, and it remains a pillar of intellectual and social activity within the community.

A National Landmark

The Flagg-Rochelle Public Library was added to the National Registry of Historic Places in 1973 in recognition of its historical and cultural significance. Today, the library serves more than 13,000 residents and an increasing number of non-residents, and it remains a pillar of intellectual and social activity within the community.

Sign Up for Our Newsletter

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest and greatest updates about the Flagg-Rochelle Public Library District.